Where you can find the best book at the right reading level and spark (or fuel) a life long love of reading in your kids!

2.26.2010

Northward to the Moon by Polly Horvath, 256 pp, RL 5

2.22.2010

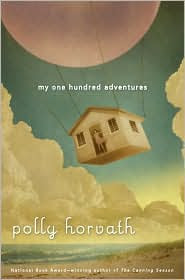

My One Hundred Adventures by Polly Horvath, 160 pp RL 5

2.15.2010

Richard Hutchins' Diary, 100 Cupboards Bonus Content

This notebook belongs to Richard Hutchins. If you find it, please return to Richard Hutchins (currently living in the seaport of Hylfing). Even though it is old and belonged to someone else first, I discovered it beneath some floorboards, and it is mine now. Do not read it. If you took it out of my pocket because you found a dead boy and you were wondering who he was; now you know that my name was Richard Hutchins. I am the dead boy. Please notify Anastasia Willis, daughter of Francis and Dorothy Willis, (currently living in the seaport of Hylfing) that I have died. And give her this notebook. Especially please do not read this next part, just a little ways down, which begins with the word ANASTASIA and ends with the word DEAD.

(Extra Note: If you have never heard of the seaport of Hylfing, that is probably because I have died in the wrong world. To me, worlds are mere chalk squares in a scotch-hop. I now venture to hop them. Possibly to my demise. I’m sorry that my body should be a burden to you. A shallow grave and short prayer is all I ask.)

Anastasia: You were wrong about me. I can be brave. I have been brave many times. I have faced terrors and enemies and demeaning comments. I have been stabbed (and if my memory serves, you haven’t). Perhaps I seemed weak when we first met. I was weak then, especially compared to the likes of Henry York and Ezekiel Johnson. But I was also young. Now, I am thirteen. Nearly. Definitely (if I die) by the time you read this. And I am unafraid. I have returned to the lonely Kansas house. I have returned to the attic. I have faced the doors. I have faced death. I might even be dead. If I am, and you’re reading this, then you can have everything. Even my three best wool socks (I haven’t had time to finish knitting the fourth). They’re yours Anastasia. Just like I am. Or was. I did all this to show you my courage. Please don’t feel badly just because I’m dead.

Exploration #1

The first cupboard I have chosen to test is on the right side of the wall, four up from the floor. In this notebook (which I did not steal—I tried to give it to Henry, but he didn’t want it) there is a short description of the door. (Anastasia, I think your great-grandfather wrote it.)

#31. Collected 1902, Fourth Britannic Tour. Single-pull drawer, oak and sterling, lateral grain. First report: Drunkard in The Swallowed Hog (London Bridge) complaining of a drawer that held weeping, laughter, voices, and even torchlight. Confirmed and purchased. Further observation: drawer cycles in activity. Progression repeats nightly, but appears dormant in between. Activity begins with voices, the low rumblings of a crowd. Ends with distant shouting and applause.

Anastasia, I think your grandfather wrote this next part later. The handwriting is different. (And he put a combination in the margin, too.)

[Partition/Globe, H-let/True pas? Alt?]

I don't know what he meant by that, but no matter. The time has come for adventuring. I will now attempt to enter the cupboard. (Goodbye. Perhaps forever.)

[Lab/Knoss/Alt Pas. back 4M?]

I admit, Anastasia, my nerves are tingling like tin soldiers. But I will do it.

(Third published entry, posted at Becky's Book Review on 2/12/2010)

Richard,First, I saw you sneaking out of my room. Don’t ever go into my room again, or Uncle Caleb’s dogs will snack on you in the night.

Second, I know you put this journal on my pillow. Stop being such a creep. The fact that you even touched my pillow means that I’ll have to burn it immediately. Did you think any of this would impress me? Sneaking around writing about yourself? Could you be weirder?

Third, I don’t believe any of it.

Fourth, if you want to impress me, change. Don’t be you anymore. Don’t be the Richard Hutchins who calls himself Richard Hutchins. I’ve seen you wear pink sweatpants, and I won’t ever forget it. But if you want me to try, start playing baseball. Be normal. Don’t notice if you get hurt. Never, ever, ever whine to me or anyone else about anything again. That would be a start.

Fifth, I don’t care that you’ve been stabbed and (if you’re not lying) hit with a broom and scratched on the ankle and bruised on the face and pinched by crabs. I just read your stupid journal and that was worse than anything you’ve ever gone through.

Sixth, you’re a chump and a sneak and a weasel and an annoying Math tutor. If you died, I probably would be a little sad for you. But I’m sure I wouldn’t notice for a very long time.

Don’t talk to me tomorrow.

Sincerely,

Anastasia

P.S. If you still feel like pretending to be brave, I picked out another cupboard for you from this journal:

#23. Collected 1900. Tin-plated drawer. Single pull. First report: Ireland. Local innkeeper with a sealed room. Cursed, he said, with vipers. Seven guests killed in a week. Locked up since. Wouldn’t let me into the room. After dark, broke in and located the drawer easily (noticeable hissing when opened). Pried it loose and bagged it quickly. Left before morning.

That one should be fun for you. And if I never see you again, at least I’ll know how you died.

2.05.2010

ND Wilson Reveals the Contents of an Unexplored Cupboard and Answers a Couple of Questions!

From the Diary of Richard Hutchins, post:

[Lab/Knoss/Alt Pas. back 4M?]

I admit, Anastasia, my nerves are tingling like tin soldiers. But I will do it.

And now, ND Wilson answers two of my pressing questions. For a more thorough interview, check out Mundie Moms and A Fort Made of Books.

I've read a considerable amount of children's literature, fantasy especially, and there are so many unique qualities to your writing that I admire, however, one aspect that stands out in my mind are the very visual descriptions of the injuries and the physical suffering your young characters endure. This is something that I have not noticed, to this extent, in other fantasy books written for young adults. As a woman and a mom, I cringe and gasp for your characters but as someone who appreciates great literature, I think it makes your characters seem more real and the story seem more immediate. (I mean, really, when you go up against evil forces, someone is going to get hurt...)

Is this quality of your writing conscious on your part, or is it just the way your mind works? And, do you ever feel like you are being too graphic in your descriptions?

It is a conscious decision, but it is probably also how my mind works. The fiction I most enjoy engages with as many of the five senses (and a couple extra) as possible, and as much of the time as possible. Obviously, you can’t just go on and on about physical sensation, but when you do appeal to it in description, the story becomes far more real for the reader. It’s more absorbing, it’s more moving, and I think it’s more honest (and less dangerous). I had friends in school who actually jumped off the roof of their two-story house with pillow cases as parachutes. Why would they get hurt? Telling and teaching kids that they can do anything and overcome any evil without paying any physical price themselves (as a lot of stories do) doesn’t actually help them. My favorite heroes growing up were those who did the right thing (and overcame) regardless of the personal cost. But, I have to admit to a more superficial justification as well—it’s just more exciting that way.

Do I ever feel that I’ve been too graphic? Sure. But I deleted all those parts. Ha.

How did you choose the dandelion as the symbol of Henry's magical attributes, his power?

I wanted Henry’s strength to be something unexpected and not at all powerful (at first glance). I wanted him to be resilient, unquenchable not unbreakable. He can be crushed and beaten, but leave him nothing more than a sidewalk crack, and he’ll pop up again, just as golden as before. The dandelion is infuriatingly persistent—good luck getting rid of them—the perfect frustration to more intuitively powerful enemies. Symbolically, it also pictures a terrific resurrection. It doesn’t grow strong and then drop acorns. It dies in a frenzy. It burns up in its own fire and goes to ash. Out of its ash, its strength is multiplied in rebirth. Of course, it also helps that the dandelion is a weed. It’s lowly, but it’s still sweet and full fire. I like my lawn green and smooth, sure. But I have to admit, I love it when it’s full of bursting gold.

You can discover the contents of other cupboards or read other interviews with ND Wilson at these sites:

On 2/10/10 you can visit The Reading Zone for ND Wilson's thoughts on the life cylce of a writer.

On 2/11/10 you can visit Eva's Book Addiction

On 2/12/10 you can visit Fireside Musings and Becky's Book Blog