Because my mother taught fourth and fifth grade for almost two decades I have known about Judith Kerr's book When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit for almost as long as I have known about her Mog the Cat books. For some reason, though, I never put two and two together and it wasn't until I sat down to write about one of my favorite childhood books, Mog the Forgetful Cat, that I discovered that the author and illustrator of this series is the same Judith Kerr who wrote this amazing memoir that follows the two years of her childhood her her family spent as refugees from Hitler and their native Germany. I have to admit, I am not an adventurous reader and it is rare that I challenge myself with a book that might be emotionally wrenching. Because of that, I had read very few of the amazing children's books set during the Holocaust like Lois Lowry's Newbery winner, Number the Stars, and Markus Zusak's bestselling, powerful book for young adults and adults, The Book Thief, to name a few. Cautious as I am, I think that Kerr's When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit was the best place for me to start my journey of reading Holocaust fiction for children.

This is because Kerr tells the story entirely from the viewpoint of Anna, her nine-year-old counterpart. The book begins in Berlin in 1933. Anna's world is made up of her friends, her school, her brother Max and his friends and his school. And her parents. Mama is a loving, piano playing mother while Papa is Alfred Kerr, a famous theater critic and poet. We learn this early on when, during a visit to the paper shop, she is cheerfully accosted by Fraulein Lambeck who inquires after Anna's "dear father," and insists that Anna give him her best wishes when she learns he is ill. At almost the same time, the reader learns that Anna is newly aware of Adolf Hitler. While she and her friend Elsbeth are gazing at a poster of Hitler Elsbeth tells Anna that he, "wants everybody to vote for him in the elections and then he's going to stop the Jews." Anna wonders aloud if he will try to stop her and Elsbeth is surprised to learn that her friend is Jewish. The story moves quickly from there with Papa leaving under the cover of night and his illness, for Prague after receiving a call from a sympathetic police officer warning that his passport is about to be confiscated (and indeed the Kerrs learn after fleeing that, the day after elections, the Nazis do indeed come for their passports.) The next morning when Mama is explaining this to the children over breakfast, warning them that they must not tell anyone, not even school friends, that their father has left the country they cannot understand. Mama says, "I've explained it all to you as well as I can. But you're still both children - you can't understand everything. Papa thinks the Nazis might . . . cause us some bother if they knew he had gone. So, he does not want us to talk about it. Now are you going to do what he asks or not?" Because When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit is told from the viewpoint of a child who clearly has protective parents and because the story only covers the time from 1933 to 1935, the horrors of the Nazis, the Holocaust and WWII are largely absent from this story.

However, that does not mean that When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit is without suspense. Besides the secret flight of her father and the anxiety filled days that pass as they wait for word that they should follow him out of Germany, there is the time when they are changing trains on their way from Switzerland to Paris when they accidentally get on a train bound for Stuttgart. At the last minute, Anna realizes their mistake and she, Max and their father scramble to collect their luggage and get off the train as it is pulling out of the station. There is also the time when they are situated in Switzerland and Anna learns that her father's books have been burned and there is a price on his head. Although she doesn't know what it means to have a price on one's head, Anna imagines a horrible shower of coins falling on him, weighting him down, and knows that this is an ominous thing. And, while (appropriately for the age of the intended audience for this book) there is almost no mention of the hideous persecution of the Jews by Hitler and the Nazis in When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit, there is the haunting figure of Onkel Julius, family friend of the Kerrs, who makes an appearance from time to time over the course of the story. From the start and repeatedly, Alfred Kerr urges his friend to leave Germany. A naturalist who took Anna on frequent visits to the Zoo, Onkel Julius believes that his government job and the fact that he is only half Jewish will keep him safe. Keeping in touch via postcards and referring to Alfred Kerr as "Aunt Alice" so that the Nazis, who are undoubtedly reading his mail, will not be able to locate the Kerrs, Onkel Julius eventually admits his mistake time. On the eve of their joyous departure to London in the summer of 1935, the Kerr's good news is dimmed by word that Onkel Julius, upon having lost his job and had his rights to visit the Zoo revoked, has committed suicide.

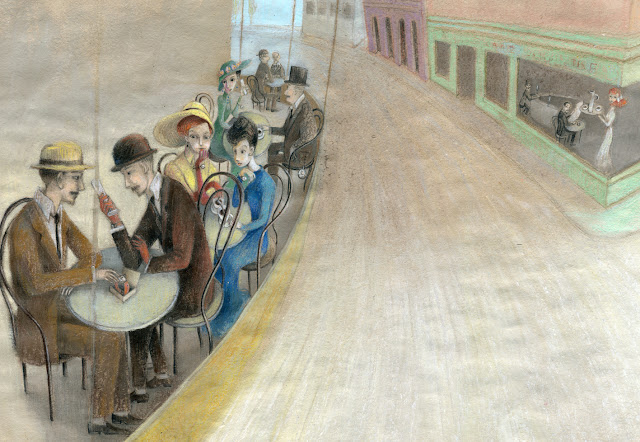

Because the events of When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit take place outside of Germany and at the very beginning of the reign of Hitler and the Third Reich, Anna's story is really one of being a refugee. Initially excited by the idea of moving and having a new life, Anna enjoys the months her family spends living at Gasthof Zwirn, an inn outside of Zurich. The Zwirns have a son and daughter who become the playmates to the Anna and Max and their days are filled with friends, school and play much like their lives in Berlin. They even have a visit from Omama, their mother's mother who lives in the south of France. Although Omama is well off and aware of the diminished circumstances of the Kerrs since leaving Germany, she does little to help them. Papa takes the train into Zurich every day and tries to find work as a journalist, but the family exists on very meager means. When there is the possibility of better work in Paris, the family moves once again, this time to a small apartment from which they can see the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe at the same time. The Depression has a hold on the French and the Kerr's financial situation does not improve, but their quality of life does. The children learn French quickly and benefit greatly from the hard work and time that they devote to their new French schools. After less than two years living in France, both children take the certificat d'études and Max, formerly a lazy student, is awarded the prix d'excellence. They make friends, visit their Great-Aunt Sarah, Omama's sister who lives in Paris and is more generous with the Kerrs, and experience Bastille Day, from dusk to dawn.

A truly gifted writer, Kerr weaves meaningful moments throughout When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit. At the start of the book, Anna is well known for writing and illustrating poems about disasters. By the end of the book, after being given a bolt of fabric from which the nicest winter coat she ever had is made, Anna writes a poem for her Great-Aunt Sarah, the giver of the fabric. Kerr writes, "It described all the clothes in detail and ended with the lines, 'And so I am the happy wearer/ Of all these nice clothes from Aunt Sarah." Upon hearing this, Great-Aunt Sarah responds, "Goodness, child. You'll be such a writer yet, like your father!" During her end of the year exams, Anna writes an essay about what she imagines her father's journey from Berlin to Prague, "with a high temperature, not knowing whether or not he would be stopped at the frontier." Her essay wins her two ten franc notes and the honor of being singled out by the mayor of Paris as the writer of one of the twenty best essays in her year. As work becomes more scarce in Paris, Alfred Kerr has the idea to write a screenplay about the early life of Napoleon and the struggles of his mother to raise her children alone. While he cannot interest any French production companies in his project, he does find a backer in London who pays him £1,000. This allows the family to leave Paris together and start their lives once again, in a new country with a new language.

In the beginning of the book, on the train from Berlin to Zurich, Anna reads a book given to them by the family of Max's best friend, Gunther. Titled They Grew to Be Great, it described the

early lives of various people who later became famous, and Anna, who had a personal interest in the subject, leafed through it eagerly at first. But, the book was so dully written and the tone was so determinedly uplifting that she became discouraged. All the famous people had had an awful time. One of them had a drunken father. Another had a stammer. Another had to wash hundreds of dirty bottles. They all had what was called a difficult childhood. Clearly you had to have one if you wanted to become famous. Dozing in her corner and mopping her nose with her two soaked handkerchiefs, Anna wished that they would get to Stuttgart and that one day, in the long-distant future, she might become famous. But, as the train rumbled through Germany in the darkness she kept thinking, 'difficult childhood . . . difficult childhood . . . difficult childhood.'

As they get off the train in London and meet up with their Uncle Otto, he says to Anna, "It must be quite difficult to spend one's childhood moving from country to country." Exhausted by the events of the day, at those words,

something cleared in Anna's mind. 'Difficult childhood . . .' she thought. The past and the present slid apart. She remembered the long, weary journey from Berlin with Mama, how hard it had rained, and how she had read Gunther's book and wished for a difficult childhood so that she might one day become famous. Had her wish come true? Could her life since she had left Germany really be described as a difficult childhood? She thought of the flat in Paris and the Gasthof Zwirn. No, it was absurd. Some things has been difficult, but it had always been interesting and often funny - and she and Max and Mama and Papa had always been together. As long as they were together she could never have a difficult childhood. She sighed a little and abandoned her hopes.

When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit, was first published in 1971, a year after the first in the MOG series, Mog the Forgetful Cat. I feel certain that, at the she was writing either book, she could not have known how famous she would become.

On a personal note, Judith Kerr was married to writer Nigel Kneale until his death in 2006. Both their children have gone on to have successful creative lives and have achieved a certain amount of fame on their own. Son Matthew Kneale is an author and his book English Passengers won the prestigious Whitbred Prize and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2000. Daughter Tacy Kneale is an artist and has worked on special effects for the Harry Potter films. Alfred Kerr's life ended in 1948 on a sad note. At the start of a tour of German cities which began with a warm greeting in a Berlin theater but ended when, after suffering a stroke and finding himself paralyzed, Kerr took his own life. Below is a portrait of Alfred Kerr.

|

| Portrait by Lovis Cornith 1907 |